On Episode 72 of The Edge of Innovation, we’re talking with entrepreneur Simon Wainwright, president of Freebird Semiconductor, about Gallium Nitride technology and the future of the space industry.

Hacking the Future of Business!

On Episode 72 of The Edge of Innovation, we’re talking with entrepreneur Simon Wainwright, president of Freebird Semiconductor, about Gallium Nitride technology and the future of the space industry.

On Episode 71 of The Edge of Innovation, we’re talking with entrepreneur Simon Wainwright, president of Freebird Semiconductor, about how he started a company to manufacture semiconductors using GaN technology!

Freebird Semiconductor’s Website

Contact Freebird Semiconductor

Find Simon Wainwright on LinkedIn

Space X – A private company that manufactures and launches advanced rockets and spacecraft

What’s So Special About Low Earth Orbit?

OneWeb: Bringing global, satellite-based internet services to Earth through a constellation of satellites

Project Loon: Balloon Powered Internet For Everyone

What is a Transistor?

What is GaN?

Link to SaviorLabs Assessment

Introduction

Starting a Semiconductor Manufacturing Company

About Simon Wainwright

A Team of Entrepreneurs

Starting a Company From Ground Zero

The Risks – Believing in Your Company From Day One

The Execution of a Business Idea

What on Earth is Going on In Space Right Now?

The Market for Satellites and Small Constellations

What Are Constellations Doing Right Now?

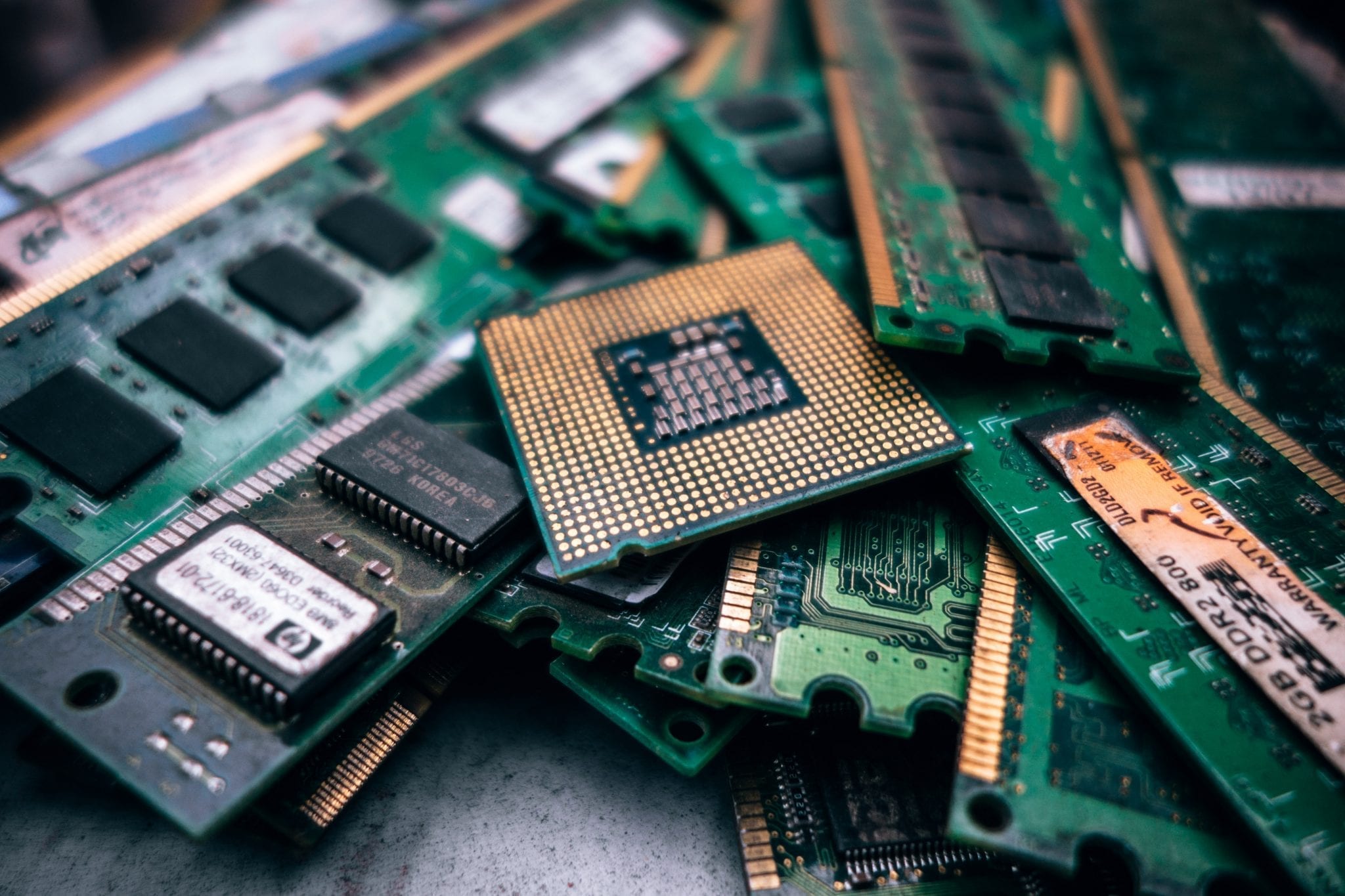

What is a Semiconductor?

The Market for Semiconductors

Wireless Charging With Gallium Nitride Technology

More Episodes

Paul: Hello. Today I’m here with Simon Wainwright. President of Freebird Semiconductor out of Haverhill, Massachusetts.

Simon: Hi. Good afternoon, Paul. How are you?

Paul: Welcome. Thank you for coming in.

Simon: No problem.

Paul: So we met probably two years ago now?

Simon: Yeah, I’d say so. Yeah.

Paul: And you were starting a new semiconductor company.

Simon: That’s correct. Yeah.

Paul: You know, our audience is quite diverse. You’ve got just normal people that have no idea what a semiconductor is to really technical people that can probably build semiconductors. Some of your competitors are people that we work in the same realm in manufacturing world. Why did you start a semiconductor manufacturing company? And how long has it been? Two years, three years now?

Simon: Yes, it’s been alive now for about two years, eight months. Something like that.

Paul: So what was the inflection point? What caused you to say, “Yeah, I’m going to start a semiconductor manufacturing company”?

Simon: It was the advantages of the technology. We work with gallium nitride, which is an emerging technology. It’s been around in the research realms for about ten, fifteen years. And then maybe in mainstream RF, or radio frequency type circuits for a little bit longer than it has been into the main power markets. But we had a relationship with the CEO and founder of another company called Efficient Power Conversion who is actually our foundry supplier of gallium nitride. And the technology just has advantages that make it… It really is an offer we couldn’t turn down. We can make things smaller, faster, more efficient and cheaper.

Paul: Okay. Well let’s get into that a little bit. So first of all, before we do that, what’s your background? I can tell you’re not from Boston.

Simon: I’m from Old England.

Paul: Old England. That’s right. Not New England. Okay. That’s a good point.

Simon: That’s right. So I’m from the UK. I studied electrical engineering, electronic engineering, at the University of Liverpool. I followed that through with a PhD in silicon uninsulated technology, believe it or not, which is now mainstream. Then I moved to Spain, my personal life took me to Spain for 20 years where I was a partner in one of the semiconductor companies in Spain as well.

Paul: So this is right in your wheelhouse.

Simon: Absolutely. Yeah.

Paul: So it wasn’t like you were a baker and you say, I’m going to wake up and I’m going to make semiconductors today.

Simon: Oh, no, no, no. I’ve always been involved in semiconductors in one form or another.

Paul: Okay. And what brought you to New England?

Simon: Basically, in my Spanish company, I was trying to sell to an American company, and they said, “Hey, we don’t want to buy your chips, but we want to hire you.” So I got a job with this company, and they ultimately brought me over about six years ago now.

Paul: So you’re relatively new to the United States.

Simon: Yeah, I’m very new.

Paul: Alright. Have you always been in New England, or did you live somewhere else?

Simon: Always here. Strangely enough, the Spanish company had an office in Andover, which is just down the road from Haverhill where we are located now. So I’ve had an association with the area for 25 years.

Paul: Okay. Cool. So you didn’t just sort of sit up one day and say, “Hey I’m going to do this.” You didn’t do it alone. You have a key team, I would imagine.”

Simon: Yes, yes.

Paul: And who are some of the people on that and also what are their roles?

Simon: So basically, there are three founders. And we each cover distinct areas of the business. So myself, I cover a little bit of the technical stuff, with my background, obviously, but I’m also in charge of the actual general management of the business itself. So I have an MBA as well that helps towards that. So basically, just the general running of the company’s accounting stuff.

Paul: Day to day.

Simon: Yeah, the day-to-day stuff. Then we have a couple of other partners, the other founders. One is a technical guy who has been 25 years in the industry doing radiation-hardened MOSFETs, which is a similar product. It’s not the same but a similar product. So we call him the chief radiation officer.

Paul: CRO?

Simon: The CRO. The CRO, yeah. So we have our product portfolio, which we’ll get into a little bit later. It’s very much radiation hardened, so we wanted to make an emphasis on that. Therefore, he got that title. And then we had the other founder,Jim. He, basically, is an industry veteran. He’s been through many different larger companies. He’s had his own small company as well, a sales company. And he’s in charge of sales, marketing and sort of like the product strategies.

Paul: I see. So now is this your first startup from ground zero?

Simon: Yes, from ground zero, yes. I’ve had other businesses, but from ground zero, this was the biggest bite I’ve taken out of the apple.

Paul: Okay. How is it? The, the entrepreneurial side?

Simon: Oh, the entrepreneurial side? It’s good. It’s good.

Paul: You like it? So you get energy from that?

Simon: Oh, absolutely! Yeah, I would never go back and work for anybody.

Paul: Yeah. I like to say that people don’t understand entrepreneurs very well, but you wake up every Monday, and you’re not employed. You don’t have a job. If you don’t get up, nobody is going to do it.

Simon: Absolutely.

Paul: Do you find that to be the case?

Simon: Absolutely. I think sometimes, I don’t even go to bed. It seems like that.

Paul: That’s a good way to put it.

Alright. So you’re in New England working for a company that sort of brought you over to help them. What came across your desk, or was it you had an epiphany or that said, “I’m going to go in and start a semiconductor company in this particular technology”?

Simon: We’d seen this in the industry. It had been around in the industry, but it was very marginal on the outskirts of technology. And then there was a reorganization we did in the company that we worked for. All three of us worked at the same company.

Paul: Oh, okay. That’s good.

Simon: So there, there was a reorganization, and it just felt like the right time. So it was we didn’t want to go in the direction that that company went into, and we wanted to follow this path.

Paul: Right. But, I mean, there’s a lot of technologies that come out that don’t prove out. Was there a huge risk, or were you at the point was it past the tipping point of it proving out?

Simon: It had gone through its initial preliminary stages where you knew it was going to work. I’m not sure the tipping point. There was still a lot of work that we’ve done in the last two years that’s maybe taken it to the tipping point now.

Paul: Okay. But you took a big risk.

Simon: Oh, yeah. Absolutely.

Paul: So, because it could have been, “Oh, we can’t solve these problems.”

Simon: Yes, absolutely. It could have been. It was a major risk. Ask my wife about that. She’ll confirm that.

Paul: You did what? You did what?

Simon: Spent the college fund on what?

Paul: Well, that’s key to….Or just everybody’s entrepreneurial experience, there’s a point at which it looks like it’s never going to work. And you persevere through that, and hopefully it will work, and then hopefully it’s scalable.

Simon: I don’t think that that’s fully the case in my case at least. I believed in it from day one. If you don’t believe in it, you don’t take that risk.

Paul: Sure. But you, but that risk is there.

Simon: Oh, absolutely.

Paul: You may have an irrational belief, but you proved out now that it was rational.

Simon: Absolutely.

Paul: Okay. So you’re past that failure point. Imminent failure point. So now it’s the execution of developing it. So where are you in that? We’ll get into what the products actually do, but you took an idea that was a concept or a set of processes probably, and refined those so that they would produce what you had hoped they would produce.

Simon: Correct. It was essentially that the guy that we worked with, with Efficient Power Conversation, he has a product. So we thought we can make that product better and specifically direct it towards the space and high reliability market. And that’s a market that the EPC was not interested in getting into fully because they didn’t want the hassle of supporting, a Boeing, a Northrop Grumman, any of these large prime subcontractors that ask for reams and reams of data.

Paul: To what end? Alright, well first of all, there’s a bunch to peel back here for the general listener I think. So, you say you supply stuff to the space industry. You didn’t even say aerospace.

Simon: No. It’s space.

Paul: Space. Now I am pretty technically savvy and interested in it, and I follow SpaceX and all this stuff. But that doesn’t seem to be that many things going into space. Or maybe I’m just ignorant.

Simon: Oh, there are, there are tons of things going on in space at the moment. Now is space’s watershed moment, so it’s the space revolution, I would say, at the moment.

Paul: And but, this is for near-earth objects or is that the words?

Simon: It’s LEO, low Earth orbit. So they’re the ones that are closer. And then there’s medium Earth orbit, and then…

Paul: So is this like tens of things are going on in space or hundreds or thousands or tens of thousands?

Simon: You’d be surprised how many launches. There are launches every week I would say. Yeah, yeah. I would say that satellites buzzing around up there at the moment, it’s impossible to put an exact number on them. And this is in the public domain. There’s a number of constellations that are coming out now. So take, for instance, a commercial constellation called OneWeb. You may have heard that they just broke ground down in Florida. They have a conglomeration between Airbus… Richard Branson’s involved in it. There’s a number of things. Softbank has funded this. And there’s a revolution at the moment in the space industry. And OneWeb is just one of the constellations.

Paul: And by constellation, you mean multiple satellites working together?

Simon: Absolutely. So it’s like a network in space essentially. So there are a number of projects for this type of constellation. So they would launch nearly 800 satellites at a very low altitude, so the low Earth orbit.

Paul: What is that? Just for listeners.

Simon: I wouldn’t be able to give you the actual height. I could look it up. I don’t have it on the top of my mind, but it’s basically the closest you can get to earth without actually falling through the atmosphere. So it’s not very high. That’s why they need more to cover more areas of the globe.

Paul: Because the distance isn’t as far.

Simon: Yeah, so that the longer ones, the higher altitude sate—, satellite such as the geostationary. They would stay over the same point, but they would cover more because the cone of coverage comes down and covers more area on the earth’s surface.

Paul: And I know we’re getting off track here. But why wouldn’t I put up a higher one?

Simon: It’s more expensive. Firstly, you have to get it higher.

Paul: Really that’s the expense?

Simon: For rockets and it’s exposed to more harsh atmospheres up there. So you get more radiation. It’s closer to the radiation sources. It’s closer to the sun and so on.

Paul: So there’s like a sweet spot.

Simon: I wouldn’t say there’s a sweet spot.

Paul: Or many sweet spots?

Simon: The higher you go, the more radiation hardened you need. The lower you go, the more tolerant you can be with radiation.

Paul: I would have never thought. Okay. So that’s a cool thing to sort of look up, is to go and look at all these different projects that are going on for all the lower Earth orbit stuff. So… Okay, so there’s a lot in the space world.

Simon: Yeah. So I mean, basically, there’s been a shift from the small constellations with geostationary satellites, with the high altitude, and they have to have lifetimes of 15-year mission expectancy.

Paul: Yeah. Because you can’t call a repair…

Simon: Exactly. You can’t send a guy over there with a wrench to fix it.

Paul: It’s very expensive. It’s just too expensive to do that, yeah.

Simon: So basically, the, the commercial level of satellites at the moment, which is all these LEO constellations, these very commercial constellations, is changing the market. It’s revolutionizing the markets at the moment. So it’s a little bit like Henry Ford did with cars, you know. You could make tons of these things. They’re almost, you can use them and throw them away. That sort of thing.

Paul: I see. So let’s take another detour. We’re getting further away. But what are they doing with these constellations? What application?

Simon: So, one of the typical applications is communication. So it’s basically internet via space. You may have heard of project Loon from Google. I’m not sure whether that’s still going on or not with balloons. They wanted high altitude balloons. So this essentially uses these new commercial constellations. They link together, and they form a network. It’s almost like the old cell phone towers, if you like, but it’s, you know, with no towers and no wires on the ground.

So it can give absolute coverage all over the globe for internet access. You get your internet access via satellite. So in the case of what’s just happened — the hurricanes down in Texas and Florida and the Caribbean — it doesn’t matter if your cell tower falls over.

Paul: Yeah, it’s a paradigm shift.

Simon: So it’s a major revolution in the way that we communicate as well.

Paul: Okay. Is this really the differentiator in your products, the radiation hardening of it?

Simon: I would say between our products, which is radiation-hardened gallium nitride, and normal gallium nitride, absolutely. It’s the radiation hardness. But between GaN, per se, and other technologies such as silicon, we have far more superior performance. We have faster switching times and lower losses.

Paul: So what are you making? I mean, are they transistors? Are they integrated circuits?

Simon: So we make transistors. Everybody is familiar with the transistor radio. Basically, it’s a switch where you turn things on, and you turn things off with a piece of semiconductor.

Paul: 2N222.

Simon: There you, there you go.

Paul: 22-22.

Simon: That’s an old silicon technology, which is still going. So there’s nothing wrong with it.

Paul: So, okay. So for, for our listeners that aren’t electronics people, it’s like you have a light switch. A transistor is a switch. Check me on this.

Simon: That’s correct. Yeah.

Paul: It’s a switch. But the toggle is another like electric field. So you connect something to the toggle, and it lets it flow or not flow?

Simon: Exactly.

Paul: And that’s why it’s called a semiconductor because it conducts under one circumstance and then another circumstance it doesn’t. Hold on. So, I had thought everything moved to ICs.

Simon: No.

Paul: You know, with millions of transistors on the ICs. So you’re saying that there’s still applications for just individual transistors.

Simon: Yep. Absolutely. We call them discrete components so that there’s absolutely a market for that at the moment. And the way that there is a market for that is it depends on the application. So the ICs that you’re talking about will basically be digital functions, like processors or things like that.

Paul: Yes, no.

Simon: Absolutely. So what we do with our discrete devices, the individual transistors, is that we manage the flow of power. So we are dedicated, really, towards providing solutions for the power management of the satellite. So to give you an idea, you’ve seen the wings of a satellite with the solar panels. So they gather energy from the sun, feed that through to a converter on the actual body of the satellite itself, and then basically, that raw energy has to be converted into — I don’t know — five volts or 3.3 volts or a test that amplifies something.

Paul: Voltage regulators.

Simon: So basically, you can use our discrete transistors in all of these power-supply-based circuits.

Paul: Okay. So I could use silicon to do that.

Simon: You can use silicon.

Paul: So if we were sitting here on Earth, which we are, and we were going to build a power supply that converted the sun energy to 5-volt, 12-volt, whatever it might be, and regulate that so it doesn’t change and we could build it with a lot of different things. I could go out and get an IC to do that. But when I fly that into space, certain problems start to happen.

Simon: Yes. So when you go into space, you have to take into account that the parameters of these transistors can change with… If you receive doses of radiation. There’s no atmosphere there, so radiation can easily attack your electronics. So that’s the first advantage of using our products, which we’ve modified sufficiently so that they are radiation hardened.

Paul: And is that just the case of it, or is it actually the actual innards of…?

Simon: It’s the innards. The innards of the semiconductor itself.

Paul: So they’re not affected as much by radiation.

Simon: Correct. That is absolutely correct.

Paul: And, is it like a 2% difference, or is it like a 50% difference?

Simon: It’s like night and day.

Paul: So it’s a game changer.

Simon: Yeah, oh absolutely a game changer.

Paul: So what did we do before this technology?

Simon: So before this technology, we had silicon. Silicon, basically, which has its limitations, so you have to do a lot of derating. You have to use them way below their stated voltages so that the radiation doesn’t really affect it. So you have to over-design these things.

Paul: And make them bigger, I imagine.

Simon: Make them bigger. Size gets huge.

Paul: Probably more shielding and things like that.

Simon: Yep. You can put shielding around the actual circuitry itself and not just the component but the circuitry itself. And there’s another element to using gallium nitride as well. Not only have we managed to achieve radiation hardness with it, but intrinsically, the material itself, the gallium nitride material, is far better than silicon anyway. So just going back to your previous example on the ground, if we wanted to build a power supply or a converter or something like that on the ground where we don’t even worry about radiation hardened effects, we could still make those circuits way more efficient.

Paul: So actual efficiency. I’m building a power supply that’s 50% efficient, yours would be 60%? I know there’s a lot of parameters, but I’m just saying…

Simon: There’s a lot of parameters, but we can easily outstrip the state-of-the-art silicon.

Paul: Well, that’s going to be a huge issue in computers. The biggest problem in computers is getting the power to them.

Simon: Yeah. Absolutely.

Paul: And so there’s a market there as well.

Simon: You will see that some of the commercial applications that EPC is, is pursuing are smaller bricks essentially, power supply bricks. The smaller ones of those. Even the remote charging. You can do remote charging because gallium nitride switches way faster than any silicon technology. So you can get the wireless charging. It’s also advantageous for things like LIDAR. So it will revolutionize the autonomous vehicles because it can scan, and it has vision systems that are way more detailed than the standard silicon-based technology.

So it really it’s a GaN revolution at the moment. It’s a GaN revolution.

You’ve been listening to Part 1 of our interview with Simon Wainwright. You can listen to part 2 of our conversation, here! We’ll be talking about the future of the space industry!

Also published on Medium.

On episode 68 of The Edge of Innovation, we’re talking with freelance photographer Al Pereira, about being an entrepreneur and running Advanced Photo, a photography store in North Reading, Massachusetts.

On Episode 63 of The Edge of Innovation, we’re talking with entrepreneur Greg Arnette, about some of the latest tech trends and gadgets that are on our radar.