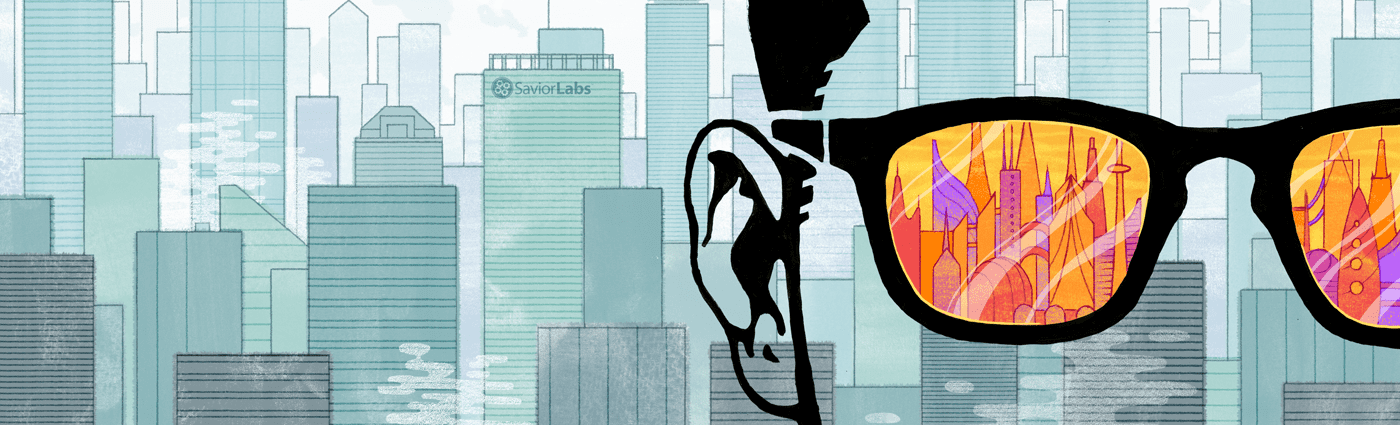

On Episode 114 of The Edge of Innovation, we’re talking with executive advisor Scott Monty about how innovators can be peripheral visionaries!

The Edge of Innovation

The Edge of Innovation

Innovation: Looking To The Future & Learning From the Past

On Episode 113 of The Edge of Innovation, we’re talking with executive advisor Scott Monty about looking to the future of innovation and learning from the past!

Innovation & Marketing Strategies With Scott Monty

On Episode 112 of The Edge of Innovation, we’re talking with executive advisor Scott Monty about innovation and marketing strategies!

Stay Curious! Innovation & Motivation

On Episode 111 of The Edge of Innovation, we’re continuing our conversation with inventor Falk Wolsky! This time we’re talking about why it’s important to stay curious as an innovator!

What Sets Inventors Apart From Other People?

On Episode 110 of The Edge of Innovation, we’re continuing our conversation with inventor Falk Wolsky! This time we’re talking about what sets inventors apart from other people!